Our Research

Authors - Shelby Putt, Sobanawartiny Wijeakumar, Robert G. Franciscus, John P. Spencer

Publication Year - 2017

Publication Year - 2017

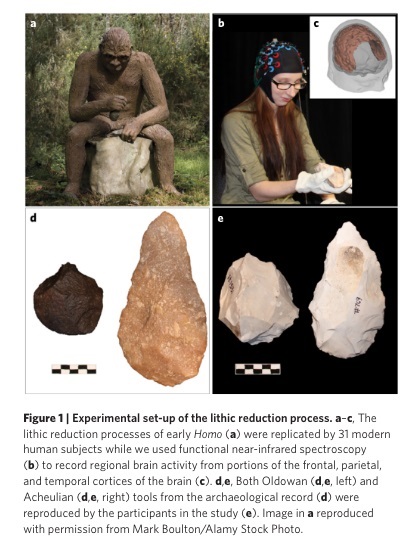

After 800,000 years of making simple Oldowan tools, early humans began manufacturing Acheulian handaxes around 1.75 million years ago (Ma). This advance is thought to reflect an evolutionary change in hominin cognition and language abilities. We used a neuroarchaeology approach to explore this hypothesis, recording brain activity via functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) as modern human participants learned to make Oldowan and Acheulian stone tools in either a verbal or nonverbal training context. Here we show that Acheulian tool production requires the integration of visual, auditory, and sensorimotor information in the middle and superior temporal cortex, the guidance of visual working memory (VWM) representations in the ventral precentral gyrus (PrG), and higher-order action planning via the supplementary motor area (SMA), activating a brain network that is also involved in modern piano playing. The right analogue to Broca’s area–which has linked tool manufacture and language in prior work1,2–was only engaged with verbal training. Acheulian toolmaking, therefore, may have more evolutionary ties to playing Mozart than quoting Shakespeare.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Nature - Human Behaviour

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Nature - Human Behaviour

Authors - P Thomas Schoenemann

Publication Year - 2017

Publication Year - 2017

Language has arguably been as important to our species' evolutionary success

as has any other behavior. Understanding how language evolved is therefore

one of the most interesting questions in evolutionary biology. Part of this story

involves understanding the evolutionary changes in our biology, particularly

our brain. However, these changes cannot themselves be understood independent

of the behavioral effects they made possible. The complexity of our inner

mental world - what will here be referred to as conceptual complexity - is one

critical result of the evolution of our brain, and it will be argued that this has in

turn led to the evolution oflanguage structure via cultural mechanisms (many of

which remain opaque and hidden from our conscious awareness). From this perspective,

the complexity oflanguage is the result of the evolution of complexity

in brain circuits underlying our conceptual awareness. However, because individual

brains mature in the context of an intensely interactive social existence -

one that is typical of primates generally but is taken to an unprecedented level

among modern humans - cultural evolution of language has itself contributed

to a richer conceptual world. This in turn has produced evolutionary pressures

to enhance brain circuits primed to learn such complexity. The dynamics oflanguage

evolution, involving brain/behavior co-evolution in this way, make it a

prime example of what have been called "complex adaptive systems" (Beckner

et al. 2009).

Read the paper here

Read the paper here

Authors - Lana Ruck, Douglas C. Broadfield, and Clifford T. Brown

Publication Year - 2015

Publication Year - 2015

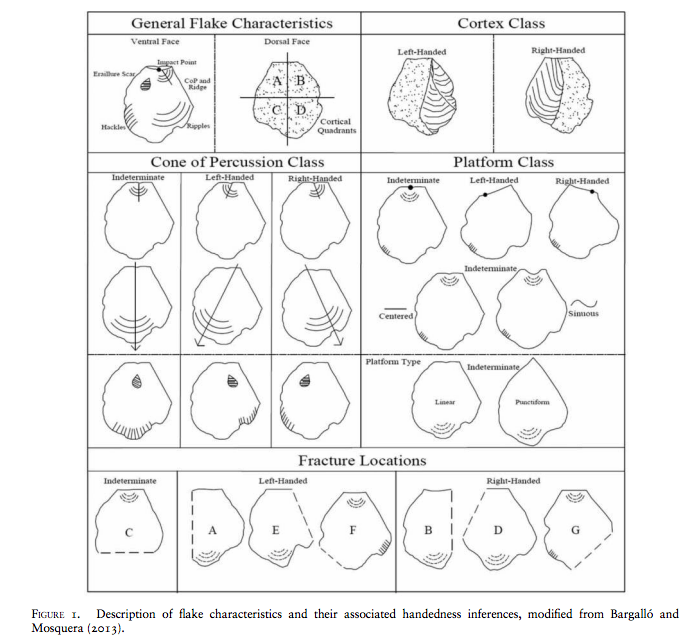

Handedness is inextricably linked to brain lateralization and language in humans, and identifying handedness in the

paleo-archaeological record is important for understanding hominid cognitive evolution. This study reports on

experiments for identifying knapper handedness in lithic debitage using three previously established methods:

Toth (1985), Rugg and Mullane (2001), and Bargalló and Mosquera (2013). A blind study was conducted on

lithic debitage (n = 631) from Acheulean handaxes (n = 10) created by right- and left-handed subjects. Blinded hand-

edness predictions for flakes were compared to their true handedness in order to assess each method’s reliability. In

order to test replicability, multiple observers classified a sample of flakes and inter-observer agreement was assessed.

None of the methods were better than chance in predictive accuracy, and there were significant issues with inter-

observer agreement. This study suggests that identifying knapper handedness in lithic debitage is extremely

difficult, but also that some existing methodological issues may have simple solutions; suggestions for future

research on this topic are provided.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Author - Robert Allen Mahaney

Publication Year - 2014

Publication Year - 2014

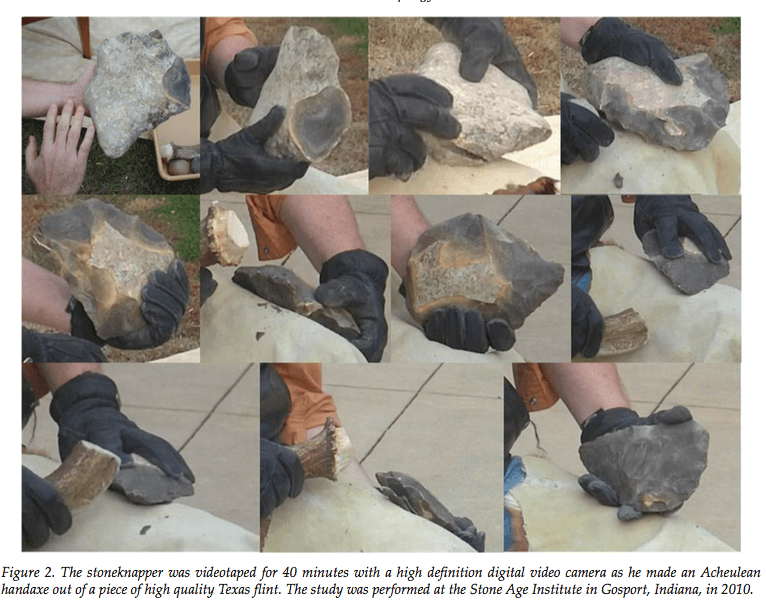

The intuition that there is a homology between sequenced action during stoneknapping and syntax in language

is long-standing, but rarely explicitly analyzed. If valid, this proposed homology would allow paleoanthropologists to gain a handle on the timing and context of language emergence. Here, I present the results of three pilot

studies performed to explore the methods such an analysis would require, as well as the issues that such an

analysis would raise. The replication of an Acheulean handaxe was videotaped, then coded. This lithic reduction

was analyzed using information theory, formal grammars, and Markov models. These three analyses found: (1)

in terms of information entropy, the thinning phase of handaxe manufacture is as complex as many English language utterances; (2) the lithic reduction can be represented as a Context-Free Grammar (CFG), though in reality

it only has limited embedding and is largely iterative in structure; and, (3) the lithic reduction also can be simulated by ‘mindless’ Markov models. These results raise a number of issues. First, it is not clear how to define and

validate comparable units in stoneknapping and language. It is also not clear that the flow of actions performed

by a stoneknapper can be easily segmented into discrete units. Second, in Studies One and Two, it was found that

handaxe replication could be simulated by both a CFG and a Markov model instantiating a Finite State Grammar.

The types of cognitive mechanisms capable of instantiating these are significantly different, with a CFG requiring

memory resources not needed by the simpler Markov processes. These pilot studies indicate that it is possible to

utilize these methods in the analysis of stoneknapping, but a number of basic conceptual and methodological issues remain to be clarified.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - PaleoAnthropology

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - PaleoAnthropology

Author - Robert Allen Mahaney

Publication Year - 2014

Publication Year - 2014

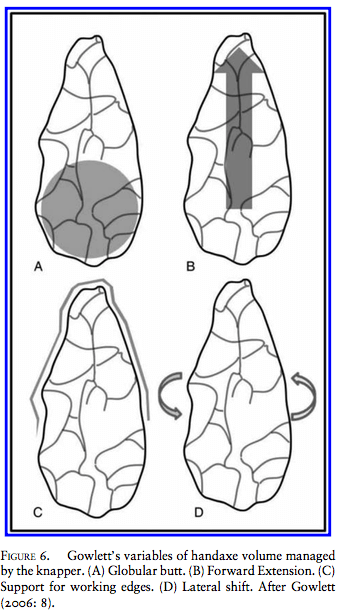

Research into the cognitive foundations of lithic technology has been increasingly prolific and productive over the

last 30 years. However, Evolutionary Cognitive Archaeology (ECA) lacks an explicit theoretical framework. In this

paper, I selectively review past work and propose a theoretical framework to open discussion amongst researchers.

First, I distinguish between the two components of cognition: knowledge and the intelligent systems that make that

knowledge possible. The chaîne opératoire approach provides a powerful method for describing and analyzing

technical knowledge. Thomas Wynn’s (1993) three-layer model of tool behavior provides a useful heuristic for

organizing research into the underlying neurocognitive processes that make technical knowledge possible. Contemporary work by Wynn, Gowlett, Bril, Moore, Stout, and Uomini are placed within this framework. Notable

findings are reviewed to describe the current state of knowledge in ECA. Without an adequate theoretical framework, ECA will continue to produce intriguing results without relating them to each other. It will also lack a

medium within which to pose and resolve theoretical and empirical debates.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Author - Shelby S. Putt, Alexander D. Woods and Robert G. Franciscus

Publication Year - 2014

Publication Year - 2014

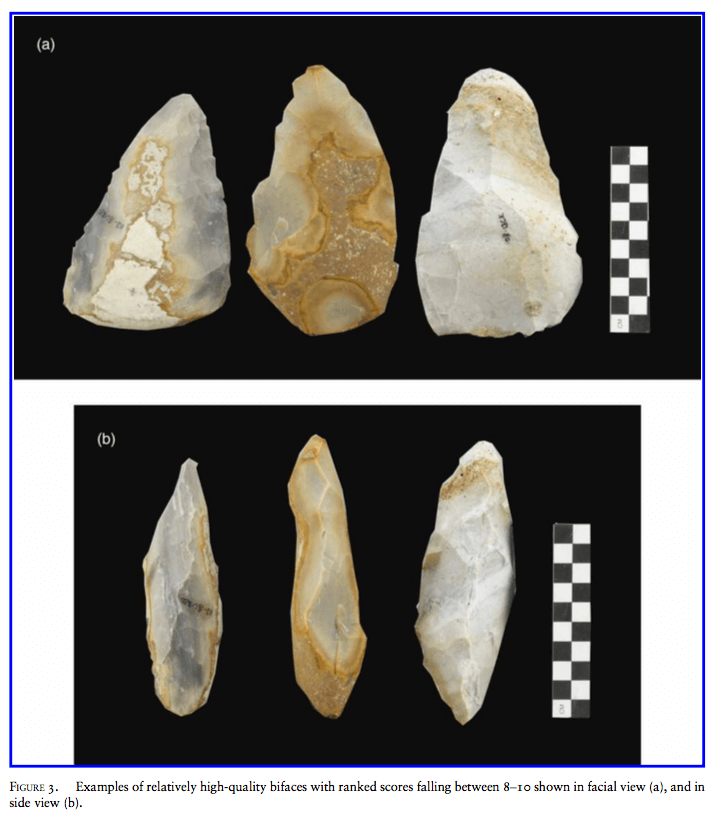

Many researchers have hypothesized an analogous, and possibly evolutionary, relationship between Paleolithic

stone tool manufacture and language. This study uses a unique design to investigate how spoken language may

affect the transmission of learning to make stone tools and comes to surprising results that may have important

implications for our views of this relationship. We conducted an experiment to test the effect of verbal communication on large core biface manufacture during the earliest stages of learning. Previously untrained flintknappers

were assigned to two different communication conditions, one with and one without spoken language, and were

instructed to replicate the bifaces produced by the same instructor. The attempted bifaces (total = 334) from the

two groups were compared using an Elliptical Fourier analysis, the Flip Test, and a rating scale by an independent

lithicist. We found no significant difference in the overall shape, symmetry, or other measures of skill among the two

groups, using all three of these methods. Analysis of the 18,149 debitage elements from the experiment, however,

revealed that the two groups set up their striking platforms in fundamentally different ways. The nonverbal group

produced more efficient flakes than the verbal group, as evidenced by the significantly higher ratios of platform

width to platform thickness and size to mass of the nonverbal subjects’ flakes. These results indicate that verbal

interaction is not a necessary component of the transmission of the overall shape, form, and symmetry of a

biface in modern human novice subjects, and it can hinder the progress of verbal learners because of their tendency

to over-imitate actions of the instructor that exceed their current skill set.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Lithic Technology

Author - Lana Ruck

Publication Year - 2014

Publication Year - 2014

Alternative functions of the left-hemisphere dominant Broca’s region have induced hypotheses regarding

the evolutionary parallels between manual praxis and language in humans. Many recent studies on Broca’s area reveal several assumptions about the cognitive mechanisms that underlie both functions,

including: (1) an accurate, finely controlled body schema, (2) increasing syntactical abilities, particularly

for goal-oriented actions, and (3) bilaterality and fronto-parietal connectivity. Although these characteristics are supported by experimental paradigms, many researchers have failed to acknowledge a major

line of evidence for the evolutionary development of these traits: stone tools. The neuroscience of stone

tool manufacture is a viable proxy for understanding evolutionary aspects of manual praxis and language,

and may provide key information for evaluating competing hypotheses on the co-evolution of these cognitive domains in our species.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Brain & Language

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Brain & Language

Author - P. Thomas Schoenemann

Publication Year - 2013

Publication Year - 2013

Because language is one of the defining characteristics of the human condition, the

origin of language constitutes one of the central and critical questions surrounding the

evolution of our species. Principles of behavioral evolution derived from evolutionary

biology place various constraints on the likely scenarios that should be entertained.

The most important principle is that evolution proceeds by modifying pre-existing

mechanisms whenever possible, rather than by creating whole new mechanisms from

scratch. Another is that flexible non-genetic behavioral change drives, at each step, later

genetic adaptation in the direction of that behavior. A model of language origins and

evolution consistent with these principles suggests that increasing conceptual complexity

of our ancestors—played out in the context of an increasingly socially interactive

existence dominated by learned behavior—drove the elaboration of communications

systems in our lineage. Empirical attempts to date the origin of important aspects

of language hinge on key assumptions about how language and material culture are

connected, or the relationships between anatomy, brain, and behavior. On the whole,

the evidence suggests a very ancient origin of significantly enhanced communication,

though exactly when this would have been identifiable to modern linguists as ‘language’

is unclear. It would appear that some critical components of language date back to the

emergence of the genus Homo, with other component shaving an even deeper ancestry.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Eastward Flows the Great River: Festschrift in Honor of Prof. William S-Y. Wang’s 80th Birthday

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Eastward Flows the Great River: Festschrift in Honor of Prof. William S-Y. Wang’s 80th Birthday

Author - P Thomas Schoenemann

Publication Year - 2013

Publication Year - 2013

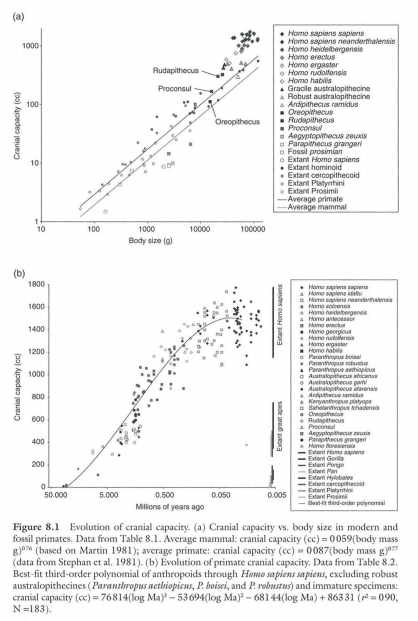

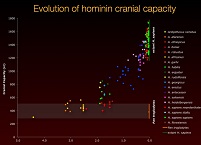

Understanding brain evolution involves identifying both the physical changes that

occurred, as well as understanding the reasons for these changes. There are two ways

in which inferences about evolutionary changes are made. By comparing a species of

interest against other modern species, one can determine what exactly is different, and

in what way it is different. By studying the fossil record , one assesses the time-course

of evolutionary changes. Both of these approaches have strengths and weaknesses.

Significantly more data are available from modern forms, both in terms of the number

of species one can assess and the specific details and subtleties of the adaptations stud-

ied, parts of the brain, connectivity between regions, neurotransmitter systems, cyto-

architecture, integrated functioning, and so forth. However, one cannot unequivocally

reconstruct the common ancestral states with this method because modern forms are

themselves the end-products of separate evolutionary lineages. In some cases it appears

that many lineages have evolved in parallel from a commo n ancestor different from

any living species. In addition, one cannot determine the time-course of evolutionary

change from a comparative analysis of the anatomy alone. For this, one needs the

fossil record . The time-course may hold clues about the functional significance of

brain evolution, depending on the timing and sequence of other features or factors

tl1at might be related to brain evolution (e.g., climate, technological, and biological

changes). However, fossil data on brain evolution are limited, since brains themselves

do not fossilize, leaving us with only their surrounding braincases (if we are even that

lucky). Thus, both approaches, comparing modern species and assessing fossil

evidence, are essential. Since there was one actual evolutionary history, our inferences

about what happened - however derived- should all point towards the same conclusions if we are truly on the right track (Vincent Sarich, personal communication).

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - A Companion to Paleoanthropology

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - A Companion to Paleoanthropology

Author - P. Thomas Schoenemann

Publication Year - 2012

Publication Year - 2012

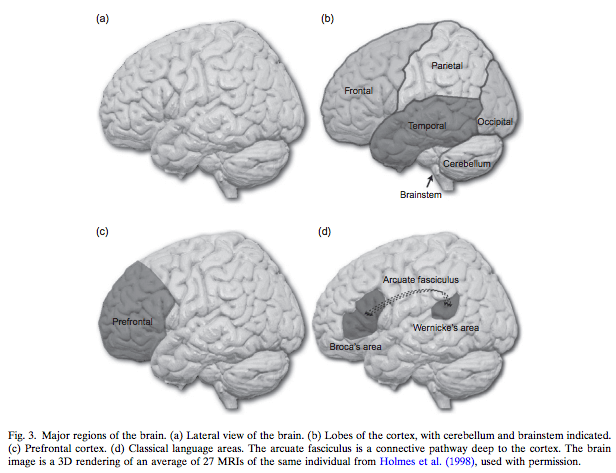

In this chapter evolutionary changes in the human brain that are relevant to language are

reviewed. Most of what is known involves assessments of the relative sizes of brain regions. Overall

brain size is associated with some key behavioral features relevant to language, including complexity

of the social environment and the degree of conceptual complexity. Prefrontal cortical and temporal

lobe areas relevant to language appear to have increased disproportionately. Areas relevant to

language production and perception have changed less dramatically. The extent to which these

changes were a consequence specifically of language versus other behavioral adaptations is a good

question, but the process may best be viewed as a complex adaptive system, whereby cultural learning

interacts with biology iteratively over time to produce language. Overall, language appears to have

adapted to the human brain more so than the reverse.

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Progress in Brain Research: Evolution of the Primate Brain from Neuron to Behavior

Read the paper here

From the Journal/Book - Progress in Brain Research: Evolution of the Primate Brain from Neuron to Behavior

Latest News

Research team members participate in language evolution workshop

read more

read more

Human evolution and the recognition of expertise

read more

read more

Schoenemann delivers keynote lecture at Evolutionary Linguistics conference

read more

read more

Students learn archaeological field methods in "The Cradle of Humankind"

read more

read more

How do apes communicate?

read more

read more

Cognitive neuroscience of stone tool manufacturing

read more

read more